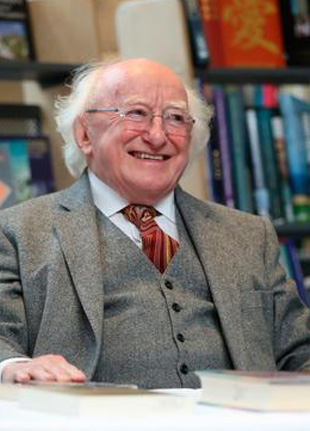

“The Betrayal” by President Michael D Higgins2

A poem for my father.

© 1990, Michael D. Higgins

From: The Betrayal

Publisher: Salmon, Galway, 1990

ISBN: 094833939x

This man is seriously ill

the doctor had said a week before,

calling for a wheelchair.

It was

after they rang me

to come down

and persuade you

to go in

condemned to remember your eyes

as they met mine in that moment

before they wheeled you away.

It was one of my final tasks

to persuade you to go in,

a Judas chosen not by Apostles

but by others more broken;

and I was, in part,

relieved when they wheeled you from me,

down that corridor, confused,

without a backward glance.

And when I had done it,

I cried, out on the road,

hitching a lift to Galway and away

from the trouble

of your cantankerous old age

and rage too,

at all that had in recent years

befallen you.

All week I waited to visit you

but when I called, you had been moved

to where those dying too slowly

were sent,

a poorhouse, no longer known by that name,

but, in the liberated era of Lemass,

given a saint’s name, ‘St Joseph’s’.

Was he Christ’s father,

patron saint of the Worker,

the mad choice of some pietistic politician?

You never cared.

Nor did you speak too much.

You had broken an attendant’s glasses,

the holy nurse told me,

when you were admitted.

Your father is a very difficult man,

as you must know. And Social Welfare is slow

and if you would pay for the glasses,

I would appreciate it.

It was 1964, just after optical benefit

was rejected by de Valera for poorer classes

in his Republic, who could not afford,

as he did

to travel to Zurich

for there regular tests and their

rimless glasses.

It was decades earlier

you had brought me to see him

pass through Newmarket-on-Fergus

as the brass and reed bank struck up,

cheeks red and distended to the point

where a child wondered whether

they would burst as they blew

their trombones.

The Sacred Heart Procession and de Valera,

you told me, were the only occasions

when their instruments were taken

from the rusting, galvinised shed

where they stored them in anticipation

of the requirements of Church and State.

Long before that, you had slept

in ditches and dug-outs,

prayed in terror at ambushes

with others who later debated

whether de Valera was lucky or brilliant

in getting the British to remember

that he was an American.

And that debate had not lasted long

in concentration camps in Newbridge

and the Curragh, where mattresses were burned,

as the gombeens decided that the new State

was a good thing,

even for business.

In the dining room of St Joseph’s

the potatoes were left in the middle of the table,

in a dish, toward which

you and many other Republicans

stretched feeble hands that shook.

Your eyes were bent as you peeled

with the long thumbnail I had often watched

scrape a pattern on the leather you had toughened for our shoes.

Your eyes when you looked at me

were a thousand miles away,

now totally broken,

unlike those times even

of rejection, when you went at sixty

for jobs you never got,

too frail to load vans, or manage

the demands of selling.

And I remember

when you came back to me,

your regular companion on such occasions,

and said: ‘They think that I’m too old

for the job. I said that I was fifty-eight

but they knew I was past sixty.’

A body ready for transportation

fit only for a coffin, that made you

too awkward

for death at home.

The shame of a coffin exit

through a window sent you here,

where my mother told me you asked

only for her to place her cool hand

under your neck.

And I was there when they asked

would they give you a Republican funeral,

in that month when you died,

between the end of the First Programme for Economic Expansion

and the Second.

I look at your photo now,

taken in the beginning of bad days,

with your surviving mates

in Limerick.

Your face haunts me, as do these memories;

and all these things have been scraped

in my heart,

and I can never hope to forget

what was, after all,

a betrayal.