Ukrainian Creative Hub with curator Dr Nathan O’Donnell at IMMA

On the 28th of November 2023, poet Hazel Hogan facilitated the first of two writing workshops aimed at engaging the Ukrainian community with IMMA’s Decade of Centenaries exhibition Self Determination: A Global Perspective. The workshops were coordinated as part of the Poetry as Commemoration initiative led by UCD Library in collaboration with Poetry Ireland and Arts Council Northern Ireland and supported by the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Dr. Nathan O’Donnell gave a bespoke tour of the exhibition before Hogan invited the participants to reflect on and respond to the artwork on display in poetic form. In this blog, Katya Van Huystee reflects on the experience. Katya works as an interpreter for the Ukrainian Creative Hub. Special thanks to Dr. Lisa Moran at IMMA for hosting the workshops.

In Dublin, November, we warm ourselves with coffee in the premises of the former stable, around a wooden table, under a high ceiling. The walls around are whitewashed, devoid of paintings, so new emotions do not distract us; we are already filled with them. The group has just returned from a tour of the exhibition “Self-Determination: a global perspective,” currently taking place at IMMA. We visited the Eastern wing of the exhibition, where works by Ukrainian artists, created in the period after the First World War, were carefully transported from museums in Kyiv. This is a piece of our home, the home that we were forced to leave after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. It hurts us deeply, especially now, as Ukraine is once again going through a period of self-determination and the struggle for existence.

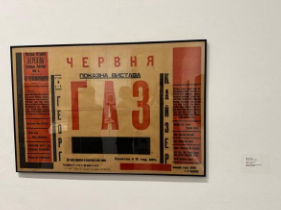

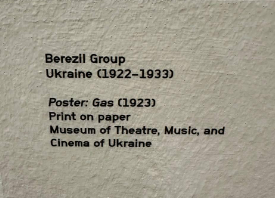

The host of the masterclass, Irish poet Hazel Hogan, encourages us, six Ukrainian women, to record the feelings and memories stirred by the exhibition. Despite working as Hazel’s translator, I always participate in her writing practices; it’s just impossible to resist. My thoughts return to the museum room where a poster for the play “Gas” is hanging. The play was staged by Ukrainian director Les Kurbas and his theatrical group “Berezil” in 1923. Why do I return here? The answer lies in the great magic of the ekphrastic poem—a poetic response to art. You never know where exactly your subconscious will lead you.

I look at the poster and it conjures an image of my grandmother slowly approaching the gas heater with a little piece of newspaper. To turn on the heating in our house near Kyiv in the 90s, you had to perform this trick: first, turn a small gas valve, and then bring a flame to the little window. I’m around 10 years old, and I’m very afraid because I know that gas can explode. But my grandmother is slow and calm; the flame in the heater ignites, and the house fills with warmth. This period marks the peak of the gas crisis in the relationship between Ukraine and Russia.

Having gained independence in 1991, Ukraine, like most former Soviet states, grapples with the collapse of the economy, hyperinflation, and debts. Ukraine’s gas debt becomes a subject of constant blackmail from Russia. In exchange for some of the debt repayment, Ukraine hands over bombers to Russia, without realizing the future danger. Tense relations between the two states permeate people’s kitchens through TV screens, settling in thoughts and conversations. During this time, I spend holidays with relatives in Russia and feel it firsthand. The first alarming signal is a conflict with teenagers in a Moscow residential area. A familiar girl claims that I stole gas from her, and that Ukraine, as a state, does not exist. A group of peers mocks my Russian with a Ukrainian accent, invents nicknames for Ukraine. On Russian TV channels, Ukraine is portrayed as weak and dependent on resources in the evening news. Gas, like a bloody trump card, repeatedly emerges from the sleeve. In 2000, the mind wars had already begun.

Celebrating my brother’s Birthday in our house in Irpin, 1990’s.

The first decade of Ukraine’s independence was like a difficult awakening after a long sleep where, in the breaks between oppression, we had to remember who we were. After 6 pm, for the sake of saving energy, they turned off the lights, and business transactions with my father were settled, not with money, but with products. However, our large family had time for joy in a cozy house near the forest. Parents worked from morning until night. My grandmother, a teacher of Ukrainian language and literature, taught me literacy, my grandfather helped me with mathematics, listened to the sessions of the Verkhovna Rada on the radio, and sang songs from his youth. Of course, the spirit of the Soviet Union had not totally left our home or the small town near Kyiv. In our attic, there were plenty of communist books and old maps, the central street was dedicated to the October Revolution, and on holidays, adults drank Soviet champagne. These were the consequences of years of assimilation and absorption, first by the Russian Empire and then by the Soviet Union. But each year brought us a step closer to ourselves.

Me wearing Ukrainian national shirt “Vishivanka” and hair decoration “Vinok” for the school performance, 1990’s.

Recalling now what has influenced my self-determination, I immediately think of the school theatre, where I read humor pieces by Pavlo Hlazovy or embodied “Katerina” from Taras Shevchenko’s poem. Theatre, literature, the first Ukrainian-language dubbed TV series, my music school, and a friend who knew the top songs of Ukrainian pop bands by heart. These were the things that shaped my connection with the Ukrainian people and made me feel a part of it. The country’s economy was also strengthening. Soon, my dad would buy our first car, I would get my first Motorola mobile phone, and in the summer, our whole family would go to the sea in Crimea. In 2013, we will go to Crimea for the last time.

In 2014, Russia annexes the Crimean Peninsula and starts a war in Eastern Ukraine, citing the protection of the Russian-speaking population. While still calling themselves fraternal people, Russia, from the UN podium in 2021, will assure that it has no intention of attacking Ukraine. On February 24, 2022, exactly 100 years after the founding of the “Berezil” theatre, Russia will invade Ukrainian territory, starting a full-scale war. One of the first cities to be hit will be Irpin, where my childhood home stands. Fierce battles will take place on the streets where I once walked to school.

History makes a circle.

I write this reflection at a moment when Russia is launching systematic missile strikes on the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, where the “Berezil” theatre was founded. Both now and at the beginning of the war in 2014, and during the time of Les Kurbas, Ukraine is faced with challenges to its own identity, its own future path, and its European values.

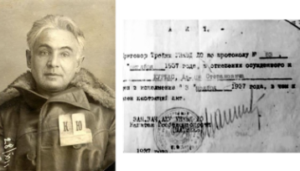

Les Kurbas | 1910

Renowned Ukrainian director, actor, publicist, and translator Les Kurbas shares a room at IMMA with colleagues from around the world who have also staged the play “Gas” by Georg Kaiser. The playbill hangs next to sketches of costumes made by artists for well-known European theatres, one of which is Dublin’s own Gate Theatre. Here, Ukraine appears as part of European cultural life, which was one of the artist’s great missions. But imagining this back when Kurbas created the experimental theatre group “Berezil” was very difficult. The group performed not only European plays but also works by well-known Ukrainian publicists, such as Mykola Kulish, who ironically and without embellishments described the Soviet reality. All of this was then called a counter-revolution and bourgeois-nationalistic tendencies, for which the intelligentsia was severely punished. Later, I would learn that the avant-garde theatre “Berezil” was prohibited from leaving the country, and Les Kurbas was executed by order of the NKVD along with Mykola Kulish.

Photo on the first day of arrest, during the investigation, Kharkiv, December 28, 1933, and the act of the execution of Les Kurbas

Time polishes details and removes emotions, leaving us with only general words and numbers. The phrase “Executed Renaissance” from the 1920s-30s, for example, conceals hundreds of tragedies and a vast cultural heritage destroyed by the totalitarian regime. We say “dark pages of history,” and that’s it. But when these dark pages of history repeat themselves, when some relatives, friends, and colleagues are at war, when people die every day and even poets have to hold a gun to protect their own land… The history of a century ago doesn’t seem so distant.

On New Year’s 2023, Russian missiles hit the power system, and Kyiv was left without electricity. Despite the threat of a repeat attack, my friend went to a candlelit concert. This illustrates how art becomes a support in dark times. Wars eventually come to an end, but art is eternal. It breathes through the walls, photo albums, and stories passed down from generation to generation. Regardless of where we are now, in Ukraine or beyond its borders, self-determination through art allows us to maintain a personal boundary, remember who we are and always feel at home.

Read Katya’s poem ‘ГАЗ’ (‘Gas’) here on the Virtual Poetry Wall.